In 2021, there is a real buzz building in the world of sports car racing. After many years of running incompatible technical regulations, the three organizations that are in charge of endurance racing in the US, France, and the rest of the world have managed to find common ground. Soon, a car that's able to compete for the overall win at Le Mans will also be eligible to do the same at Sebring or Daytona, and vice-versa.

This convergence was meant to stimulate interest and draw in new entries, and it's doing just that: Acura, Audi, BMW, Ferrari, Glickenhaus, Peugeot, and Toyota have all confirmed programs. Entries are also expected from Cadillac, Hyundai, and Lamborghini. That level of manufacturer involvement hasn't been seen since the glory days of Group C, and it's fair to say the increasing field of competitors has fans excited at the prospect.

But sports car racing—which often involves multiple classes of cars racing at the same time—is nothing if not overly complicated. The news is good, but bear with us as we explain what's going on.

Prepare for acronyms: IMSA, ACO, FIA, WTF

To start with, there are three different organizations involved in the regulations and decision-making. Here in the US, the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) is in charge of overall sports car racing and the Weathertech SportsCar Championship, which includes specific events like the Rolex 24 at Daytona, the 12 Hours of Sebring, and the Petit Le Mans, among others.

Over in Europe, the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) is the organizer of the 24 Hours of Le Mans. And then there's the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA), which is in charge of global motorsport and world championships like the World Endurance Championship.

In the 2000s, IMSA and the ACO used very similar technical regulations. But in 2014, IMSA merged with another US series, and that new collaboration had to come up with an original rulebook to accommodate a new mix of cars. Unfortunately, what they settled on left no room for the very fastest Le Mans prototypes (called LMP1s).

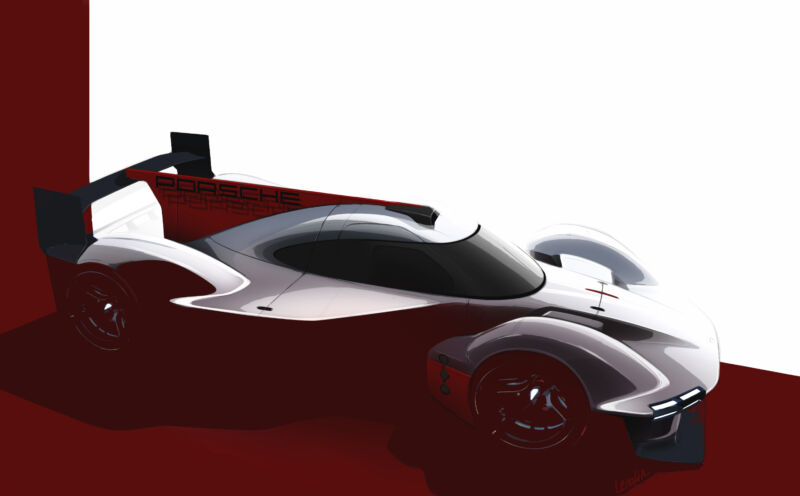

Fast cars usually look good, and the 2016 Porsche 919 Hybrid (an LMP1) is no exception.Elle Cayabyab Gitlin

Fast cars usually look good, and the 2016 Porsche 919 Hybrid (an LMP1) is no exception.Elle Cayabyab Gitlin The Cadillac DPi-V.R race car was undefeated in 2017, though of course it couldn't race against certain other hypercars very easily at the time.Richard Prince for Cadillac Racing

The Cadillac DPi-V.R race car was undefeated in 2017, though of course it couldn't race against certain other hypercars very easily at the time.Richard Prince for Cadillac Racing

LMP1h, DPi

The mighty LMP1s continued to race at Le Mans and in the WEC, eventually evolving into some of the most technologically advanced cars ever seen. LMP1 soon turned into LMP1h—"h" for hybrid. A complicated set of rules called the Equivalence of Performance was put in place to theoretically allow different technical approaches to compete on a level playing field. In the resulting races, we saw kinetic flywheels and supercapacitors as well as lithium-ion batteries, both gasoline and diesel engines, and rear- or all-wheel drive powertrains.

For a few short years, fans were treated to some epic racing between Audi, Toyota, and Porsche. But the two German OEMs had Formula 1-sized budgets that became unsustainable, particularly in the aftermath of dieselgate. By 2018, only Toyota remained, competing against non-hybrid privateer LMP1 cars. The ACO tried to make things fair for the much less well-funded privateers through an ever-increasing handicap, but such regulations didn't always succeed.

Meanwhile back in the States: in 2017, IMSA introduced its new DPi (Daytona Prototype International) category. This took the ACO's second-fastest category (called LMP2) as its starting point, but where LMP2 was aimed at privateer teams and amateur drivers, DPi was for OEMs and factory teams. So, IMSA allowed DPi entrants the freedom to choose their own engine and develop their own electronics (both of which were spec items in LMP2). The new DPi guidelines also gave the OEMs more styling freedom so that the racing prototypes looked a little bit more like actual road cars.

Technical regulations don't last forever, of course. IMSA, the ACO, and the FIA all knew attracting more OEMs to the top class of sports cars would ultimately require a few things. First, the rules had to allow for some form of hybridization, given almost every company's move to electrify passenger car fleets. Next, the cars should bear more resemblance to road-going cars. And finally, costs needed to become sensible.

LMH, LMDh—it's all hypercar to me

Enter the hypercar. The ACO got the ball rolling first, announcing that it wanted to attract racing versions of road-legal hypercars like the Aston Martin Valkyrie. There's something romantic about the idea of taking off a car's number plates, putting in a rollcage, and going racing (even if it's been about 50 years since such a thing was really practical).

So the ACO created a Le Mans Hypercar (LMH) category to make that happen. LMH allows entrants quite a lot of technical freedom (though less than LMP1h); the cars are heavier and less powerful than LMP1, with a lower downforce-to-drag ratio of 4:1. The first LMH cars took to the track this year, including a pair of Toyota GR010 hybrids, a pair of Glickenhaus 007 hypercars, and an Alpine LMP1 car that has been grandfathered in. As we reported recently, Peugeot is set to return next year with its 9X8 hybrid, and Ferrari has confirmed it will enter LMH in 2023 with a hybrid car.

Still, IMSA had some of its own requirements that meant it couldn't just adopt LMH for its top class. But DPi proved pretty successful, and so in 2023 IMSA is evolving that category into a new one called LMDh. Like DPi, it starts off with an OEM choosing one of four approved "spines"—the carbon fiber chassis manufactured by Dallara, Ligier, Multimatic, and Oreca. As with DPi, each OEM is free to choose its own engine and electronics, and there is even more styling freedom than DPi, albeit with the same 4:1 downforce-drag ratio as LMH.

There are plenty of spec(ified) components that will be identical in each car to keep costs down. That includes the hybrid system, which combines a Bosch electric motor and Xtrac sequential gearbox, as well as a lithium-ion traction battery from Williams Advanced Engineering. Total power output will be capped at 670 hp (500 kW) sent to the rear wheels—the electric motor is allowed to regenerate at up to 268 hp (200 kW) but can only deploy 67 hp (50 kW).

Fans of uninhibited technology development may turn their noses up at the use of spec components, and it certainly complicates any stories an OEM might want to tell about technology transfer from the race track to road cars. But the upside is the price tag—the complete hybrid system will cost around $355,000 (€300,000) and the chassis about $408,000 (€345,000). Add in the cost of the internal combustion engine and some other bits, and a complete LMDh car should still cost less than $1.5 million.

That's definitely attractive for an OEM like Audi. "The new hypercars fit perfectly with our new set-up in motorsport and our roadmap of electrification," an Audi Sport spokesperson told Ars by email. "The regulations for LMDh cars in particular allow us to field fascinating race cars in prestigious races worldwide while regulations are trimmed for maximum cost efficiency." (Audi and Porsche are working together on an LMDh program using the same engine and the same Multimatic chassis but with different styling, which may also result in a Lamborghini version in 2024.)

The fact that the LMDh is allowed in US championships also factored in to some OEM decisions. "We know what engine we're going to put [in], we know what constructor we're going to work with, and then the program is in the first place centered around the IMSA championship because we want to have this for our biggest market, which is the US," said BMW Motorsport boss Mike Wrack. (BMW is believed to have selected Dallara as its chassis-maker.)

When asked, Wrack didn't see much wrong with the use of spec components. "You see it also in Formula E: there is a lot of spec, but there are also some open areas. And we learned a lot there," he said. "So yes, there is a lot of spec, but I think the spec is the only way to keep costs under control. And with hypercar [LMH], there is an element of additional cost, which in current times, it's really difficult to get through [the board of directors]. So, for us, the LMDh was a preferred direction, not only because of cost efficiency, but also because of the US market."

Convergence

"We ought to have an opportunity for everybody to race together," IMSA President John Doonan told me about all this. "The key—and it may sound simple, but it's obviously quite complicated—is finding a technical solution for that to happen."

According to Doonan, work on this kind of universal set of parameters was happening in parallel. When FIA and ACO put out a set of rules for hypercars, he said IMSA had already been working on a similar initiative (it was "basically DPI 2.0, which was more styling, integrating the hybrid, keeping cost-effective," Doonan said).

"And I think, as it got closer, [the ACO] couldn't wait any longer. They announced hypercar [LMH], we then announced LMDh," he continued. "In the meantime, I think all of us said, 'You know we ought to be able to talk more about bringing it all together. Manufacturers have asked for it.' So that's what we delivered in LMDh. Now we're at a juncture where some folks are down the path. We got plenty of people committed here; let's find a way to see the cars race together."

That technical skeleton making this cross series racing possible is called convergence, and it sets targets in four different areas to let LMH and LMDh cars play together nicely. The four key components are tire sizes, acceleration profile, braking capability, and aerodynamics.

The ACO already had some thoughts about tire sizes, since its LMH category allows for RWD and AWD cars (AWD cars have the smallest tires at 31 inches front and rear, with RWD LMH cars using 29-inch front tires and 34-inch rear tires). IMSA and the ACO have decided to apply that same approach. Since LMDh is RWD, LMDh cars will use the 29-inch front/34-inch rear tires.

To prevent the AWD hybrid LMH cars from having a huge acceleration advantage, the race organizers will restrict the electric motors from deploying energy below a certain speed, most likely 75 mph (120 km/h) in the wet and 100 mph (160 km/h) in the dry. Like tire size, this is a balance of performance tactics that the ACO and FIA have already started using in WEC.

With regard to braking, the front differentials of AWD LMH cars will have a zero-lock mechanism to prevent them from gaining an advantage under deceleration. And LMDh cars will have control software to prevent the electric motor from functioning as a kind of traction control device. Both kinds of cars will have the same coasting performance, with specified levels of front and rear torque splits for the AWD machinery.

To balance aerodynamics, every LMH car will be benchmarked in a wind tunnel owned by the Swiss F1 team Sauber. And every LMDh car will be similarly benchmarked at the Windshear tunnel in North Carolina. If an LMH team wants to enter IMSA races, they have to put their car through Windshear; vice-versa for LMDh teams who want to race at Le Mans or in WEC.

Finally, both IMSA and the ACO and FIA will implement their own series-specific balance of performance (as they currently do) to keep things equal among competitors. This means that a Porsche LMDh car that races in WEC might do so with a slightly different configuration than a Porsche LMDh car racing in IMSA.

Can an LMDh win Le Mans? Can an LMH win Sebring?

The biggest remaining question is one we will have to wait until 2023 to answer. Specifically, will IMSA allow LMH cars to come to the US and win its marquee races, and will the ACO really let LMDh cars win at Le Mans? It's natural to expect each series to favor its full-time entrants, and earlier this year Glickenhaus boldly told Motor Sport that such a thing would be impossible. But Glickenhaus made those statements in February. When I asked the same question of teams at the beginning of July, I got a very different answer.

"We need to trust IMSA and the ACO. A lot of work has been done already long before we have now entered. It will be good for all if it's possible, and I think they will make it possible," BMW's Wrack told me.

"Yes, being able to fight for overall victories and championship titles at the Le Mans 24 Hours, at the Daytona 24 Hours, in the World Endurance Championship (WEC) and in the IMSA series was key for our decision," said Audi via email.

Similarly, Wayne Taylor, who will run one of the two Acura LMDh cars, told Motor Sport that "if I thought we would have no chance at winning, I would not be doing it," in regard to LMDh cars having a chance of winning Le Mans. (Acura head of R&D Jon Ikeda was similarly confident when I spoke to him.)

The first real test for that will happen at the end of January 2023 for that year's Rolex 24 at Daytona, which will be the first race for LMDh... and also the first IMSA race open to the LMH teams. A year and a half is a long time (nearly long enough to square all these acronyms and standards in a racing fan's mind) and things can still evolve, but I can't wait.

https://ift.tt/2VrXlp2

Tecnology

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "What is LMDh and why are we so excited about sports car racing in 2023? - Ars Technica"

Post a Comment